|

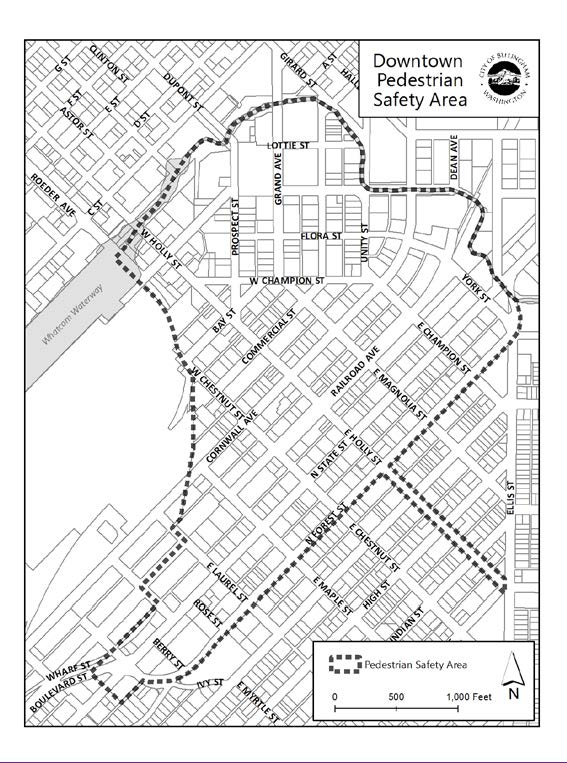

City Council, I understand that the Bellingham City Council is considering increasing sanctions for sitting and lying on sidewalks, having open containers, and being intoxicated in the downtown area. I understand the idea is to jail these people by making civil infractions into misdemeanors. I also understand that temporarily jailing mentally ill, alcoholic, and homeless people does not decrease alcoholism, mental illness, or homelessness. When they are released, they will still be alcoholic, mentally ill, and/or homeless. Also, I am concerned that the program seeks arbitrary enforcement against people whose appearance does not fit the downtown aesthetic (i.e., classism). At the same time, Whatcom County residents are considering a tax increase to build a larger “right sized” jail. Please consider the relationship between these two measures: If you build, they will come. No, that’s not quite right – if you send them, we will have to build – that’s it. The current question is what should a compassionate and frugal city do with its poor and marginalized residents – help bring them into the fold, or push them away and pressure them to move down the road a bit, maybe towards Maritime Park? Please remember that both of these options have costs. Let’s seriously consider which one will be less costly in the long term. Edward S. Alexander

1 Comment

by Edward S. Alexander Selma takes lessons from history and presents them in a fresh, relatable way for today’s soon-to-be activists. Perhaps the biggest impediment to action is that tiny fleeting moment between the flash of realization that there is a problem, and the decision as to what if anything to do about it. Selma raises the question, and answers it loud and clear. We see it all too often: a conversation, a news article, a book, or a movie reveals a deep and disturbing truth. The experiencer of truth feels deep connection with the world around her, a quickened heart rate, and then the briefest pang of guilt or fear when she realizes that her part in the world is very much a cause of the problem. She realizes that to make a difference she will have to change longstanding routines and habits that have made her feel safe. She will have to admit her complicity. She will have to dismantle her own longstanding patterns of thought. And if she allows herself to dwell on this deep and disturbing truth long enough, she will realize that to make a real difference, she will have to upset people, including people she looks to for affirmation, love and support; for they, too, need to go through this painful process. All of this happens in an instant. The typical next step is for the experiencer to throw her hands up in the air and ask (rhetorically), what can I do about it? At that point, the battle is nearly lost. In the space of that very fleeting moment before she asked the question, she had already retreated to a safe place where she knows the answer: Nothing I can do will be effective in solving this problem. Selma jams a crowbar into that tiny space, that fleeting moment, and keeps it pried open for 127 minutes. Martin Luther King and a host of other activists show the moviegoer in scene after scene what she can and should do about it: “What we do is negotiate, demonstrate, resist.” King tells the moviegoer with confidence that she can and must do something about it: No citizen of this country can call themselves blameless, for we all bear a responsibility for our fellow man. I am appealing to men and women of God and Goodwill everywhere, white black and otherwise: if you believe all are created equal, come to Selma. Join us. Join our march against injustice and inhumanity. We need you to stand with us. And after the movie ends and the credits start to roll, when the experiencer is looking for a dark corner to retreat to, a safe place to hide from the beautiful and horrifying light of truth they have just experienced about humanity. . . ah, there it is: "That was history; racism is behind us now. . ." That's when John Legend’s song glory tells us how it is: That's why Rosa sat on the bus That's why we walk through Ferguson with our hands up When it go down we woman and man up They say, "Stay down" and we stand up Shots, we on the ground, the camera panned up King pointed to the mountain top and we ran up One day, when the glory comes It will be ours, it will be ours Oh, one day, when the war is one We will be sure, we will be here sure Oh, glory, glory Oh, glory, glory glory Yes, there it is: That scene where Lynden B. Johnson and Alabama Governor William Wallace are sitting in the oval office; Johnson asks, “You agree they should have the right to vote, don’t you?” and Wallace answers, “Yes, and they do have the right to vote. . . technically.” Even if moviegoers are capable of mental gymnastics that might enable them to land on some technicality – maybe something like the fact that grand juries heard all the evidence and decided not to indict – how many will want to stand there? How many will want to return to the shadows? Maybe some. But don’t let them. So how do you heed Martin Luther King’s posthumous call to action now, in 2015? Learn the facts of the John Crawford shooting, the Michael Brown shooting, the Eric Garner shooting, the Tamir Rice shooting. Tell people that 2014 is only different from the previous years because we do not know the names of the people who died in 2013, or 2012. Watch the film Fruitvale Station and see Oscar Grant’s last 24 hours before he was shot by police in 2013. Tell people that the laws still have not changed. Technically, disparate treatment is illegal. It has been since the 14th amendment was passed in 1868. Police, though, are not required to attend racial bias training. Police are not required to collect, sort and share race data on stops, searches, arrests, and uses of force, rendering civilian oversight of our public servants very difficult. And of course . . .negotiate, demonstrate, resist. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed